Chris Jones discusses Logan's run, pensions freedom and financial planning in his latest article for Retirement Planner

One of the traditional sayings about financial objectives is: ‘For the cheque to the undertaker to bounce.’

What was meant by this was that you spent all your money during your lifetime yet never ran out. This is obviously easier said than done, and to do it with any certainty you would need to know your date of death in advance.

The entire life assurance industry is built on the fact that nobody knows when they are going to die. There is also a huge psychological and sociological question about whether or not it would be a good thing if you did know. Logan’s Run is the classic film on this subject.

If I was to learn that I only had precisely a year to live, I might decide to cram all the pleasurable things that I wanted to do into that one year and spend all of my money in the process.

One year later, if I were to wake up surprised and penniless, only to consult my doctor and find out it was a mistake, would I be pleased or disappointed? For those of us who would be pleased, it begs the question: why don’t we just do it anyway but without the stress of the diagnosis?

Freedom and choice

A longer-term version of this conundrum is presented to us with the April 2015 pension freedoms. Before these freedoms, few people had to think about when they would die in the context of their spending. This was the problem of the life assurance industry.

Before 2015, longevity and the question of a date of death was hidden behind the annuity or GAD element of illustrations and triennial reviews. Rules were in place to, in the FCA’s words, “ensure that the funds in their pension last for the rest of their life.” But once full pension freedoms were afforded it became more personal, more specific and more central to the advice with the need to calculate the risk of ruin.

Few believe that the general public worried too much about the longevity risk passing from the industry to them. They just liked the freedoms, liked the fact that they could spend their pension pot faster or leave more of it to their family, and ultimately liked the idea that a financial institution didn’t control them or their money.

Yet the Work and Pensions Committee found three years later in 2018 that there was “little evidence that savers were frivolously squandering their life savings” but that “this did not mean that people were making well-informed pension freedom decisions.”

As a result, through its Retirement Options Review the FCA is seeking to prevent and reduce consumer harm with Investment Pathways and by ensuring consumers are supported to make well-informed retirement income decisions. Back in 2014/2015, our focus was on finding or building longevity-based ‘risk of ruin’ calculators. The focus now is on the investment itself and information, perhaps surprisingly, neither remedies or factors in longevity. This is perhaps an indication of how longevity risk is now an individual matter as well as an individual risk.

The major difference between how a life assurance company can use longevity statistics and how an individual can is pooling. Averages work for an insurer’s pool of lives because winners can offset losers, whereas at an individual level you are either a winner or a loser. A similar scenario to how bookmakers can always make money whilst gamblers can’t.

This transfer of longevity risk (and the responsibility) means that retiring consumers not only need information, but they also need advice - and specifically advice that involves a cashflow plan that is continually reviewed. In this space, there are just too many unknowns, with perhaps the biggest one being the individual’s longevity. There are no ‘fire and forget solutions’ unless you buy an annuity and pass the longevity risk back to the insurer.

Discussing average longevity can be useful to challenge clients who believe that they will only live as long as their father, or those that imagine they are immortal and will still be working at 80, but it can be dangerous when used as an absolute in a decumulation strategy.

To illustrate the point I have looked at ONS national life tables, UK 2017-2019.

If you’re a man aged 65, you can expect to live another 18.76 years. A 65-year-old woman can expect another 21.12 years. Perfect, if you’re a single male you can plan for your pension to last another 18 years 9 months and not a day longer.

Obviously, we do not live in Logan’s Run and the world does not work like this. The 18.76 years is clearly an average: some will get hit by a bus tomorrow and some will celebrate their 100th birthday. As you don’t know which you fall into, why not use the average as a guide? Even better, why not get more data and instead of just relying on your gender, why not get a better average based on your health, postcode, wealth etc?

The answer lies deeper in the data. Half of 65-year-old males can expect to die somewhere between the ages of 78 and 90. Half of 65-year-old females will die between the ages of 81 and 93. Suddenly the differences in the averages between males and females doesn’t look so significant, as there is a large overlap. A quick simulation shows that roughly 4 times in 10, a 65-year-old male will outlive a 65-year-old female. Maybe extra data will refine this range by a year or so, but even that is hardly useful when you’re equally likely to die outside this range as inside it.

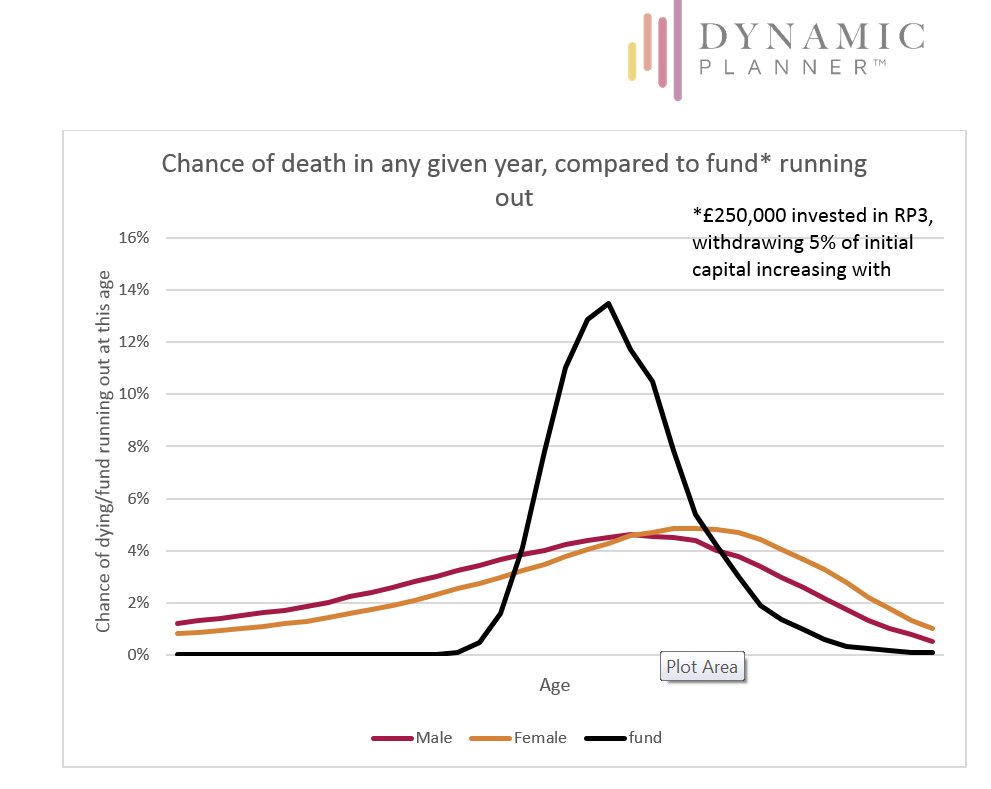

Financial planning has to deal with these types of uncertainties, but it’s important to understand the degree of uncertainty. Investment returns are uncertain, but the time over which an investment pot might run out is more predictable than life expectancy. In a low-risk fund (risk level 3), withdrawing 5% of the initial capital (allowing the income taken to increase with inflation) half of investment pots would run out between ages 83 and 88. That’s just a five year range, compared with 12 years for life expectancy. If you take a larger amount of income (say 6%) then only if you are invested in a fund with a high level of risk does the range of outcomes start to look as wide as the range of life expectancies.

In simple terms, we can make a reasonable estimate as to when your retirement pot will run out, but not whether you’ll be around when it does.

Rather than worrying about whether the average person like you will live an extra 20 or 21 years, it is better to remember that as an individual you could live into your 100s, or you could die tomorrow.

So, if you really want to spend that last penny before you die, or if you have any other objective, you will need a financial plan and a financial planner that is with you throughout.

Chris Jones is proposition director at Dynamic Planner